Making Men Equal: The Legend of Samuel Colt’s 200th Birthday

22nd Jul 2014

It was in the winter of 1831 that Sam Colt saw a revolving pistol for the first time. This occasion was so important that he lied about it in later years. The gun shop he visited in Calcutta had a few examples of the Collier revolving flintlock pistol. Studying them gave Sam ideas for improving the revolver. The main fault of the Collier, Sam thought, was the method by which the cylinder was rotated. After each shot was fired, the shooter had to set the cylinder into a firing position by hand, always making sure that a loaded chamber was in line with the barrel. This had to be done each time the pistol was fired. Then, too, the Collier had too many parts; more than 40 separate pieces went into the lock, not including the lockplate, attaching screws, stock, cylinder and other essentials. His invention would cut down the number of parts, but, more important, he would devise a method of turning the cylinder automatically, not by hand.

While the Corvo ship sailed back to Boston, Massachusetts, Sam occupied his leisure time with the hobby of many sailors, whittling. His subject matter was to be an improvement on the Collier guns he had seen in India. As he worked on the scrap of wood, his vision took shape. He bored six holes in the wooden cylinder with a hot wire. The hammer of his wooden gun was very similar to those of the actual pieces he would later produce. Bit by bit, the gun was taking its desired shape, but the all-important finishing touch was still missing. Sam had to find a way to make the cylinder rotate automatically.

He spent many hours on the deck of the Corvo thinking over his problem. Then, one day, as he watched the men unloading a hold, he saw the answer unfold before his eyes, but in reverse. The operation he witnessed was the working of the common windlass. As he watched it, he found his idea. The windlass had a large cylinder, conventionally termed the wheel, turning a smaller cylinder or barrel, termed the axle, the difference in size giving a gain of power. A large drum, fitted with powerful brakes, held the load in place. Sam reasoned that instead of having the force applied to the drum and holding the pawl fixed, he would move the pawl, attached to the hammer, and then, by cocking the hammer, the cylinder would revolve to the next firing position and lock into place automatically. The idea was simple, yet no one had ever thought of it before. Sam eagerly grasped his penknife and applied these attributes to his wooden revolver. Once finished, he patiently waited for the Corvo to land at Boston.

With financial aid from his father, Christopher, Sam sought the services of Anson Chase, a gunsmith of Hartford, Connecticut. Chase agreed to produce the working models Colt needed and set himself to the task. He made a pistol, which closely followed Colt’s wooden pattern, then turned his efforts toward producing a revolving rifle. On December 30, 1831, using money he received as a Christmas gift, Colt paid Chase $15 on the account, but where or when he would get the balance lay in doubt.

When he left his home in Ware, Massachusetts, the youth Samuel Colt was no more. In his place stood Dr. Coult, the celebrated lecturer and scientist of New York, London and Calcutta. The deception was magnificent and enabled Sam to collect fees for lecturing on natural philosophy and chemistry. After each lecture, he would delight his audience with a demonstration of laughing gas. Using a willing participant, Sam administered the gas, which induced a form of harmless intoxication.

Within 10 days after his first appearance as Dr. Coult, Sam had managed to save enough money for a trip to Washington. Before leaving, he stopped off at Anson Chase’s gun shop and picked up his crudely finished pistol and rifle. Sam was confident that once he arrived in Washington, a patent could be secured for his invention.

Upon his arrival, Sam looked up an old friend of his father’s, Henry Ellsworth. He wanted Ellsworth’s help, for besides being a family friend, he was also the Commissioner of Patents. Ellsworth reviewed the rudely finished arms with great interest and, as a friend, offered Sam some sound advice. He told him to hold off on his patent until the time when the arms could be smoothed out and finished properly, making them the mechanical marvels they were intended to be. As they were at the time, they left much to be desired. Sam agreed and accepted a caveat, which in today’s terminology means and an Affidavit of Claim of Invention. This would ensure Sam’s priority until the time when sufficient capital could be raised to promote his invention. Ellsworth deposited the model arms in the archives of the patent office, and Sam once more took to the back roads as Dr. Coult.

When Sam arrived in Hartford in December 1833, Chase showed him another crude specimen fashioned from the original model. They were eager to test it, and the revolver was promptly loaded, placed in a vise and fired. Much to the dismay of the two men, the revolver burst apart. It was a disheartening thing to have happen, but it was the first hint of a trouble that would plague Colt for several years — re-flash. A front plate, which held the loose bullets from falling out, trapped the lateral flash at the breech end of the barrel. This pushed the hot particles of gunpowder into the adjoining chambers, setting off the other charges. When all the charges fired at once, they literally tore the barrel right off the gun. Sam was dejected over his gun’s failure, but, being a good showman, and needing more money for future experiments, he headed to Baltimore to continue his lectures.

The shop of A.T. Baxter was well known by the townspeople for its skilled craftsmen. It was only natural that Sam visit Baxter with the hope that he could produce a few working models of his revolver. Colt was shown some examples of Baxter’s work, and, being impressed, he was excited to let Baxter tackle the job. Baxter detailed one of his best men, John Pearson, to fill Colt’s needs, then left the men to themselves. Colt explained his revolver design to Pearson, stressing certain points he felt the gunsmith should know. They talked for several hours, and before Sam left the shop, he was assured that the task of making several revolving pistols and rifles would be accomplished to his satisfaction.

From March 1 to May 24, Sam had given Baxter and Pearson more than $400 for the work Pearson had done on several pistols and two rifles. Sam realized that there was still a lot to be done before the arms reached the desired degree of perfection needed to obtain a patent, so he decided to offer Pearson a private deal. Pearson liked the idea and agreed to leave Baxter to work for Sam exclusively. They drew up a contract whereby Sam agreed to pay a set amount to Pearson each month, as well as provide a shop for him to work in. By June 1834, Pearson was settled in his new shop and working diligently on Colt’s arms.

In July 1835, Sam visited Washington and was assured by Henry Ellsworth that his arms were now ready. It was only a matter of time until the government granted Colt his patent. Feeling secure and somewhat relieved over Ellsworth’s confidence, Sam decided to return to Hartford for a visit with his father. After all, Christopher Colt was the only successful businessman Sam knew well enough to ask for money.

Arriving at home, Sam found that it didn’t take much to convince his father that his invention had great possibilities. Christopher had faith in Ellsworth, and if Ellsworth thought enough of Sam’s idea to patent it, why shouldn’t he back his son? Besides, Sam’s cousin, Dudley Selden, a prominent New York lawyer, had seen the revolver and thought it had great business potential. The overwhelming majority of confidence shown toward Sam’s invention benefited him greatly. His father agreed to advance him $1,000 against an 8 percent interest in the yet-unissued revolver patent.

Cousin Dudley was also helpful in bringing another important matter to light. If the revolver proved a big success, other countries could copy its design without reprisal. On the other hand, if Sam were to go to England and France to take out patents for his invention, no one could infringe upon them. They all agreed that Dudley was right, so Sam prepared for a trip to Europe.

After a few days’ wait on arriving to London, and with the helpful work of his agent, John Hawkins, Sam Colt received the patent (No. 6909) he so desired from the British Crown. It wasn’t easy, as they both had to appear before the High Court of Chancery to obtain a patent. But all went well, and on October 30, 1835, a color drawing of Sam’s revolver design was placed in a vault along with the other treasured records of England.

Arriving in Paris, Sam sought the services of A. Perpigna, a well-known advocate. Perpigna, like Hawkins, was well qualified to fill Sam’s needs. It was only a matter of time and money until Colt received his revolver patent from France.

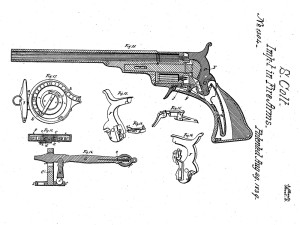

Colt Paterson “Holster Model,” patent August 29, 1839.

In January 1836, Colt returned from Europe. His mission accomplished, he now set out to obtain his American patent, which was coming due, and formed a company for manufacturing arms.

Christopher gave Sam an additional $300 to help promote his invention, but warned him against spending it foolishly. Sam took the money, cleaned up a few of his debts (as usual, he owed Pederson some back pay) and set out to find investors for his company. With the help of Dudley Selden, several prominent New York businessmen became interested in the Colt revolver. However, they wanted proof of Colt’s patent claims before they invested their money.

They didn’t have long to wait, for on February 25, 1836, Sam Colt was granted patent No. 9430. (This was later changed to patent No. 138 because of a fire that destroyed the patent office.) The patent covered four basic principles that would enable Colt to produce his revolvers without competition until the patent expired in 1857. The four principles were, in brief:

It was decided that the gun works would be built on the Passaic River in Paterson, New Jersey, and it wasn’t long before things began humming at the Paterson factory. Colt had hired Pliny Lawton to act as superintendent, and the responsibility of setting up a workable plant operation lay on his shoulders. It was a difficult job, as friction constantly arose between Sam and Dudley. Sam had studied the methods of Eli Whitney, in regard to using machine-made interchangeable parts, and wanted to employ similar methods at Paterson. Dudley, however, felt that the arms should be fabricated by hand and, as general manager of the company (because of his large investments in the concern), wanted to do things “his way.” They were never in complete agreement, but a semi-happy medium was finally reached, and the arms produced at Paterson were partially finished by hand, partially by machine

Sam realized that for any large arms company to be successful, it would have to be patronized by the government. If he could interest the Army in his revolver, his fortune would be made. Unfortunately for Colt, when the Army trial board met at West Point in 1837, there was a great deal of opposition to his firearms. It was the old story of “If it was good enough to fight with last year, why change to something new this year?” In any case, the board agreed to examine Colt’s entry and not actually test it. The gun Colt chose to show the board was a seven-shot revolving musket weighing more than 15 pounds. It was a monstrosity for a military rifle, but as part of the examination, it was test fired. Four volleys were fired at a distance of 180 yards. In each volley, two simultaneous discharges took place. It was the old “Colt curse” of re-flash that caused the mishap, but it gave the board the necessary evidence to officially condemn Colt arms for the military.

It was a blow for the 23-year-old inventor to return to Paterson a failure, once again faced with the age-old problem of preventing re-flash. At once he started experiments with various ideas he had formulated. He thought that if the fronts of the cylinder chambers were beveled, it would provide a desirable plane to turn away the flash. These early experiments helped pave the way later for a much needed improvement, the loading lever. The lever made it possible to wedge an oversize ball into the chamber, effecting an airtight seal. Once this was accomplished, the chance of re-flash was nil.

Experimental Pocket Pistol, serial number 5. It was created between 1849 and 1850 at Colt’s Armory in Hartford. Caliber is .265. The barrel length is 3 inches, and it has an overall length of 7 inches.

Even though the Ordnance Board gave Colt’s rifle a poor recommendation, the activities of the Paterson factory continued. In the latter part of 1837, the American Institute of New York for the Encouragement of Science and Invention awarded Colt’s rifle a gold medal. At the same time, his pistol was pushed aside by the Institute with the comment: “Colt’s revolving chambered pistols — best fit only for military uses.” Again, in 1838 the Colt rifle won the Institute’s award, but the revolver was still considered to be strictly a military firearm.

The Seminole Indian War had broken out in Florida, and Sam, being a resourceful New England Yankee, saw an opportunity to prove his guns worthy in the toughest test of all: actual combat. He packed 50 revolving pistols and an equal number of rifles into two crates and headed for Florida.

Leading the 2nd Regiment of U.S. Dragoons was one of the most progressive officers in the Army, Colonel William S. Harney. He was a fighter, not a Washington pen-pusher, and, as such, he believed in having his men well armed with the best equipment available. Colonel Harney saw the usefulness and advantages of having repeating arms in combat, and Colt made his first government sale.

Serving with the Army in Florida at that time was a young man who was to become the most important individual in Sam Colt’s life, Samuel H. Walker. Though they were not destined to meet until December 1846, the lives and fortunes of the two men were bound together by a common tie: Colt’s revolver. Walker, like Harney, was a fighter, and to him the Colt revolver was the greatest asset a fighting man had. However, it was many years before Walker was asked to voice his opinion of the revolver.

Sam Walker was a Texas Ranger captain and military officer who had served with Colt pistols in several conflicts. He proposed several improvements including that a sixth round be added to the popular five-shot Colt Paterson revolver.

In 1839, another important link was added to the Colt chain of developments. John Fuller, one of Sam Colt’s representatives, was visiting the newly formed Republic of Texas. Call it coincidence, but one of his oldest friends, Colonel George W. Hockley, was now Chief Ordnance Officer for the Republic. Through him, Fuller became well acquainted with other important heads of the Texas government and soon received an order from Memucan Hunt, Secretary of the Navy. The order was for 180 revolver carbines and 180 revolvers, complete with proper appendages for both.

Although Colt’s pistol was worth more than a single-shot, its cost was prohibitive to many prospective purchasers. At that time, the average pair of single-shot flintlocks cost between $6 and $9; a single Colt revolver cost $26. This price was not competitive, and, as a result, many orders were lost. It was Lawton’s job as superintendent to keep the quality and quantity of Colt arms up and the price down. This was essential, for the Depression of 1837 made available buying capital scarce; failure would cause the company to go into bankruptcy.

In August 1839, Sam Colt was granted an additional patent (No. 1304) from the U.S. government. This patent records the improvements brought about by experimentation at Paterson prior to the start of actual production. There was no mention of a permanently attached loading lever in any of the patent claims, so it is assumed that it wasn’t yet perfected. However, the use of exposed hammers on Paterson-made shotguns and carbines made its debut in this patent.

The Patent Arms Manufacturing Company was fighting a losing battle. The constant disagreements between Sam and cousin Dudley over production methods and foolish spending ended when Dudley resigned as manager. Taking his place was John Ehlers, an employee who had risen from the status of chief clerk to treasurer. Ehlers was a capable man, but the affairs of the company had gotten so out of hand that the beginning of the end was near. Although prices for Colt’s pistols and carbines had been lowered considerably, they were still far from being competitive. Ehlers knew the company needed large orders to survive, but none was obtained.

In the government trials of 1840, the United States

Ordnance Board took a more favorable attitude toward Colt’s firearms. It placed

an order for 100 repeating carbines in March 1841 and in July of the same year

followed it up with an additional order for 60 more. The carbines cost the

government $45 each, a substantial reduction from the $125 price paid in

Florida several years before. However, this token of government patronage came

too late to help the faltering concern, and in 1842 John Ehlers threw the

company into

bankruptcy.

By late 1843, the contents of the Paterson factory had been liquidated, and Sam Colt was left stripped of everything save his patents. These the company let him keep, for they were deemed useless. Little did it know that Sam was still destined to make his fortune utilizing the seemingly worthless patents.

In the summer of 1844, Samuel H. Walker, now a Texas Ranger, received a small shipment of Paterson revolvers. These were part of the order that Colt had originally placed with the Texas Navy. Walker’s experience with the Seminoles had convinced him of the Colts’ superiority, and he was certain the revolvers would provide the added firepower he needed to quell the bands of marauding Comanche warriors in Texas.

Shortly after receiving the revolvers, Walker and 14 other Rangers under the command of Major John Coffee Hays encountered a party of 80 Comanche braves near the Nueces River in the Pedernales country. The Comanche, confident in their five-to-one strength over the Rangers, attacked twice in rapid succession. This was done to draw the Rangers’ fire from the single-shot rifles and pistols they normally carried. Then, a third attack was launched with the hope of catching the Rangers in the process of reloading. For the first time, the Indians’ strategy didn’t work. Instead of riding into a band of helpless man, they were torn by the sudden flashing fire of a new weapon. Volley after volley spit death into the attacking horde, and when the last shot was fired, more than half of the arrogant war party lay dead or wounded on the field. It was a decisive victory for the Rangers, but a greater one for Colt’s revolver.

The same fateful influences that crossed the life paths of the two Sams were still at work. In the spring of 1846, Samuel Walker joined the newly formed U.S. Mounted Rifles in the Army of Brevet Brigadier General Zachary Taylor. Walker was now fighting for the State of Texas.

Many of the men in Taylor’s command were former Rangers who had made careers of battling for Texas’ freedom. Among them was John Coffee Hays, now a colonel heading his own regiment in the Mounted Rifles. He and Walker both knew that Colt revolvers were urgently needed by every man in the command, and they lost no time in convincing “Old Rough and Ready” Zachary Taylor of their needs. Because Captain Walker was the logical man to go, General Taylor dispatched him to Washington. His job was to find Sam Colt and do everything possible to expedite the immediate production of 1,000 revolvers. Sam Colt didn’t know it yet, but he was going back into the gun business.

In 1846, a trip from the Rio Grande to Washington took quite a long time. By the time Walker found Colt, General Taylor had already fought the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma and was pushing deep into Mexico. Walker explained his mission and further expressed his personal feelings toward the Colt revolver. The two Sams became immediate friends.

Suddenly, after 10 years of bitter failure to get adequate Ordnance recognition of his design, Colt was sought out and asked to furnish 1,000 revolvers to the Army. Walker’s intervention came at a time when the future of the Colt revolver had never looked darker. Colt had no machinery, no factory and, surprisingly, not even one of his original Paterson pistols to use as a model.

Colt always loved the arms business, and with an order for 1,000 revolvers at hand and a promise of an additional order for 2,000 more, it didn’t take much to convince him. Colt immediately left for Connecticut to find Eli Whitney (son of the cotton gin inventor), who had both the finances and the factory equipment to undertake such a project. This was in December 1846. Whitney was a hardheaded businessman, but so was Colt. One of the most important terms of their contract was that Colt would retain ownership of any special machinery acquired for the work. He was thinking ahead to the additional order for 2,000 revolvers promised by the Army. Whitney agreed and promised to start manufacturing the arms whenever Colt was ready.

Using a model of a Paterson pistol he either borrowed or bought, Colt set out to make the required changes that Walker suggested. Vivid memories of his Comanche fighting games may well have influenced Walker into recommending a six-shot cylinder for the new revolver. An added shot for each man could be the narrow margin between victory and defeat. Also to be considered was the caliber. The Paterson, a .36-caliber weapon, was good, but Walker wanted a real man-stopper. They decided that the new pistol would be a .44. The grip was then lengthened for better grasping, and a 9-inch barrel was added. The next main problem was the trigger. On the Paterson, the trigger dropped down from the frame when the hammer was cocked. The new gun would be made with a fixed trigger, protected by a large, brass, squareback guard. This would enable a soldier to carry his pistol cocked without fear of accidental discharge. Under the barrel, an improved loading lever was attached for driving the lead balls into the six-cylinder chambers. All these ideas and more were added to the new design, and when it was finished, a larger and heavier handgun than its predecessor emerged, but one obviously better suited to the rigors of frontier Army duty.

Colt had Waterman L. Ormsby (the engraver who made the dies for his Paterson pistol and subsequently all the later models of percussion Colt arms) make up a die depicting a small body of cavalry armed with revolvers engaging a larger force of Indians. This scene was rolled on the cylinder of each revolver as a tribute to Walker’s Ranger exploits, but of course it was also political, under the circumstances, to illustrate U.S. mounted troops. As another gesture to show his gratefulness for getting him back in the arms business, Colt named the new revolver the “Walker-Colt.”

When the arms were finished, they were to be numbered according to Walker’s instructions, by pairs and Companies. Each man in the Mounted Rifles was to receive a pair of the new revolvers. The Companies ran from “A” to “E,” and each was to be stamped with the Company letter and number. It is a known fact that these numbers ran from “A” Co. 1 to “A” Co. 220, “B” Co. 1 to “B” Co. 220, etc. There is only one doubt, and that is to the numbering of the “E” Company guns. As only 1,000 were ordered and 220 were to be placed in each of the first four Companies, it is assumed that the numbering on “E” Company arms stopped at 120. This is further confirmed by the fact that, today, the highest “E” Company Walker known bears the number 115. (The pistols that bear “C” Company markings are most desirable since that was Sam Walker’s Company.)

By October, Sam Walker had returned to Mexico to rejoin his regiment. He was informed by an Ordnance Department letter that his Company’s revolvers had been shipped to Vera Cruz. The letter was dated July 8, but for some unknown reason, the Colts were still undelivered. On October 5, 1847, Walker wrote his brother from Perote, saying he had just received a pair of the new revolvers direct from Sam Colt. As for the others, they were still delayed. The pair of pistols Colt had sent to Walker were part of an overproduction of 100 that were made to give away as gifts from the “Inventor.” These guns wore no Company numbers, but were numbered as civilian pieces starting with serial number 1001 and ending with serial number 1100.

Ironic as it may seem, four days after Walker received the revolvers he helped to create, he was mortally wounded during the battle of Huamantla by a shotgun fired from a balcony. Capt. Bedney F. McDonald, one of the 3rd Artillery, sent Colt one of Walker’s revolvers as a memento of Sam’s deceased friend. The gun is still preserved in the Colt Cabinet of Arms at Hartford.

Colt, having fulfilled his bargain to furnish the Army with 1,000 revolvers, now set out to establish a new gun factory for himself. He knew that time was all-important, as the government’s order for another 2,000 pistols was at hand. He looked about for a suitable site and finally decided to establish his factory in Hartford.

The first Hartford location was at 33 Pearl Street. Here, Sam set up his machinery and commenced work on August 1, 1847. He was to remain on Pearl Street until 1850, when he moved his factory to a new location in Hartford.

In quick succession, the War with Mexico ended, and the California Gold Rush began. The orders for Colt revolvers were pouring into the factory. In 1851, the newly elected Governor of Connecticut, Thomas Seymour, fulfilled one of Colt’s fondest wishes by appointing him Lt. Colonel and Aide-de-Camp. Colt’s only duties were social ones, and he performed them gracefully. However, he was now able to call himself “Colonel.”

Colt’s belief was that once a man tried and tested his revolvers, he would become a staunch supporter of his products. The years 1855 and 1856 were important ones for Colt. In 1855, his new factory at Hartford was completed, bringing an even greater perfection to Colt manufacturing processes. The factory was incorporated as Colt’s Pt. F. A. Mfg. Co. Inc. Much of the credit for improving labor-saving devices and machine designs went to the factory superintendent, Elisha K. Root.

In 1856, now wealthy and successful at the age of 42, Sam decided to fulfill one of his greatest ambitions. He married Elizabeth Hart Jarvis. They left for Europe on their honeymoon and, because of Sam’s aggressiveness, succeeded in obtaining an invitation to attend the coronation of Czar Alexander II.

When his patent finally expired on February 23, 1857, arms companies such as Remington, Whitney and Manhattan all begin producing revolvers using Colt’s system and design. It affected him somewhat, but his revolver had long been established as a superior handgun, and his sales continued to mount.

With the start of the American Civil War in April 1861, demands for Colt pistols increased rapidly. Sam had given up his heavy Dragoon pistol designs and was now producing sleek new models. Of these new guns, greatest favor from the Ordnance Department was found in the .36-caliber 1851 Navy Model and the improved .44-caliber 1860 Army Model. Colt employed the services of Waterman L. Ormsby to make a die for the rolling of the Navy and Army cylinders. Remembering the Paterson purchases made by the Texas Navy many years before, Sam decided to honor those early fighters with a suitable memento. The die Ormsby engraved depicted the fight between the Texas Navy and Mexican warships on May 16, 1843.

In the spring of 1861, Sam Colt was in poor health. His 10-month-old daughter, Elizabeth, had died in October. It was a devastating blow to his heart. Colt’s physician, Dr. John F. Gray, opinioned his illness as gout, but even Sam knew it to be more serious. It was a short time later that Colt was confined to his bed. He was stubborn, however, and refused to lie around and be idle. Through couriers, he directed the activities of his vast holdings and successfully ran the factory. Finally, all his suffering ended on January 10, 1862.

A fine example of the famed Collier flintlock, patented in 1818. Elisha Collier invented this arm in America back in 1813, but because the public lacked interest in his invention, he took it to England for patenting. The Collier used a rotating chambered breech that had to be turned by hand.

The Elizabeth Hart Jarvis Colt Collection came to the Wadsworth Atheneum when Mrs. Colt died in 1905. Highlights include the wooden model carved by Colt aboardship in his youth that led him to the design of the perfect revolver as well as scarce examples of Colt’s own products.